The Berbice River was one boundary of Kwakwani to which it clung in fright from the forest which loomed behind it, threatening to engulf it in an unwary moment. The mines were the reason Kwakwani was created and the reason it existed. Kwakwani was owned by the mining company, Guyana Mining Enterprise, Kwakwani Operations. The Administrative Manager of Kwakwani Operations was the defacto ‘Mayor’ of Kwakwani. He was not only responsible for the company’s operations but also for the welfare of the people of the town. The hospital was owned by the company, which employed the doctor and staff. The company ran the only store, which was called the Commissary. This store stocked all basic essentials which, given the resource starved economy, did not amount to much. The store stocked Dishikis and shirts, cutlasses, axes, pickaxes, crowbars, hardware and plumbing items, food – mainly staples and some meats in the freezer section and of course, a very well stocked liquor store. Guyanese can drink. Man! Can they drink!! The most popular drink was rum; Demarara Rum, drunk neat or with Coke. A black drink that looks like lube oil. Guyanese eat large quantities of meat and drink large quantities of rum and they are among the most friendly and jolly people in the world.

The town was divided in two parts. Kwakwani Park, which had the workers quarters, some of which were barracks, some twin houses with two rooms each, and some individual homes in the Self-Help area. Most of the houses were built with wood, plenty and cheap in Guyana, on stilts with a short stairway of 6 or 7 stairs leading up to the front door. The stairway (called ‘Step’) was not only for going up to the house but more importantly for people to sit on and socialize. Once the work of the home was done, the women would come out onto their steps and carry on conversations with the neighbors sitting across the street on their step. In the evening once the men returned from work, they would carry their drink in their hand and sit on the step and talk about the day gone by. The Self-Help area was an area that the Government of Guyana and the company had promoted where people owned the houses they helped to build. That is why it was called Self-Help. This was a big departure from the usual norm in Kwakwani where all housing was company built and owned.

Almost all houses in Kwakwani Park had vegetable gardens; most of them right behind the house in the rain forest which was never far away. People employed the slash-and-burn type of agriculture, as mentioned earlier, a method that is widely practiced all over Guyana but is very destructive to the rain forest. But then again, what do you tell people who live on the margins and who have to do something or the other to make ends meet? These gardens provided food for the family as well as some small income for those who worked harder as they could sell the produce in the market. The gardens were also a source of protein because they attracted wild pig (Collared Peccary), deer, capybara, agouti, and curassow. The wily farmer, especially immediately after the burn when the ash was on the ground and a great attraction to the animals, would sit in hiding either on a platform on a nearby tree or on the ground and shoot whatever came. Hearing gunshots in the night was not uncommon and not anything to be worried about. Some Amerindian farmers would also set snares with spears and arrows or even sometimes with a stick of explosive (easily available from the mines) for pig. One, therefore, had to watch very closely and walk carefully when negotiating a farm in the forest to avoid becoming an unintended victim of the hunter.

People mostly grew bananas, cassava (tapioca), pineapple, and sweet potato. The typical Guyanese farmer in Kwakwani was a person of African extraction; a mine worker in the day who would drive a truck or some earth moving or mining equipment, or work in the machine shop and then in the evening he would put on his farming shirt – a much patched, seldom washed and therefore odoriferous garment smelling of honest sweat – and would go to work in his farm. He would carry a shotgun in one hand and a cutlass in the other. He would wear a floppy hat from under which he would look at you and smile; a smile that would light up his whole face. Then if you said anything that was even remotely funny, he would shake all over and laugh so heartily that his whole body would laugh with him; the world would become a better place for a little while. Laughter and rhythm are the two hallmarks of the African person. I always say that nobody can laugh or dance like an African. It is something that is visceral and intrinsic to being African. I have even prayed behind an African Imam in the US who would do a quiet little dance as he recited the Qur’an. Highly objectionable in law but then the question is, how come you were looking at the Imam instead of concentrating on your prayer, eh?

The company had kindly allotted me the house that my parents had lived in for the year that they were in Kwakwani, so I didn’t have to move from Staff Hill, which was the senior officer’s enclave. My father, who started work in Linden at the main Guymine hospital was transferred to Kwakwani as the head of the small hospital there at about the same time as I got my job. So for one year we lived together in Kwakwani. Then they left, returning home to India and I stayed on for three years thereafter. That is how I was in the house which the company allowed me to retain after my parents had left – another of Nick Adam’s favors. The house overlooked an orange orchard on the far side of which was the ever present jungle. Behind the house was a large open area cleared out of the jungle and then there was the jungle. The orange orchard used to be well maintained with its grass cut and the orange trees pruned and fertilized. The orange tree has a lovely shape and on a moonlit night to sit in my veranda simply looking out across at the orchard was something that I greatly enjoyed. This was one of the many joys of a TV-less existence. This orange orchard was also the first time I saw Leaf Cutter ants (Atta cephalotes) at work. I woke up one morning to find one tree almost completely defoliated. When I went to examine what had happened, I saw a long line of ants with pieces of leaves in their mandibles busily walking to their nest. This was a mound about 2 meters in height and double that in circumference at the edge of the forest boundary. I had read about these ants and how they use these leaves as a substrate to grow fungi to feed on, but this was the first time I was seeing them in action. I also knew the cure for them, which was to collect the refuse from the mound and place it around the base of the tree, which they then avoid. This, I found to be true. It is said that this remedy works for up to 30 days but in the case of Kwakwani where it rained almost every afternoon, it didn’t last that long. These ants have a very elaborate and complex society and I recommend you read about it.

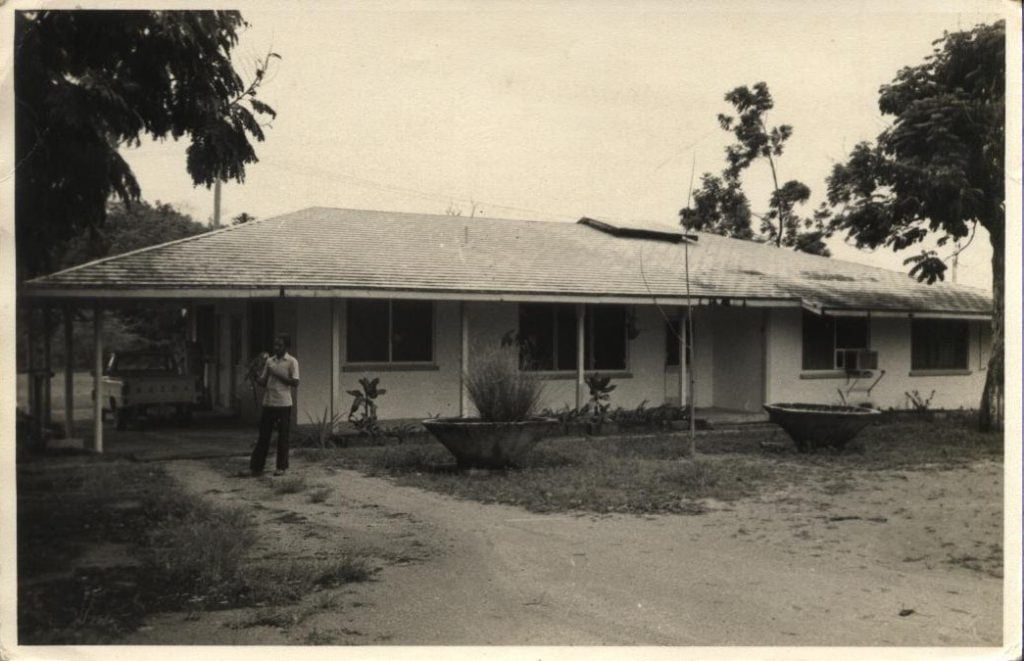

The house itself was a low roofed bungalow with a veranda in the front and on one side. It had three small bedrooms with two bathrooms and a main hall which served both as a dining and living room. It was very sparsely furnished, so I made some furniture. I got the sawmill people to saw me a few Wamara planks—with their lovely double colored grain—and got a few fire bricks and lo and behold I had a complete shelf system in which I used to keep my books and other some local handicrafts. To one side was the kitchen with a big gas cooker. The gas cylinder was housed in a small enclosed shelf in the veranda behind the kitchen and the gas was piped to the stove. I would make my own breakfast and Naomi, my very large, very concerned, and very domineering cook from St. Lucia, would come in and make my lunch and dinner. For breakfast I would usually toast some crackers with cheese on them in the oven and make myself a cup of tea.

One day, with this intention, as usual, I prepared my tray of crackers with slices of cheese on them and opened the gas oven to light it. I smelt something funny, but didn’t give it much thought and struck a match. Instantly there was a huge explosion and I was thrown back against the wall. The glass of the oven shattered and my tray of crackers flew out of my hands. I had a burning sensation on my face but otherwise seemed to be alright. I ran to the bathroom mirror and discovered that I was minus eyebrows and eyelashes and my face was very red. The hair on my forearms was also singed off, but otherwise I seemed none the worse for the shock. What had happened was that there was a gas leak in the oven and the oven was full of gas. That was what I had smelt when I sat in front of the oven but hadn’t recognized the aroma. When I lit the match, it ignited the gas and it exploded. Mercifully, I had to open the glass oven door to light it and so the glass didn’t shatter in my face. Having a face full of toughened glass wouldn’t have been any fun. My beard saved the rest of my face and apart from feeling crinkly with the hairs being singed, the beard was also intact. It took me some minutes to get over the shock of having the oven explode in my face and to be thankful for having been saved. But after that it was off to work with an interesting story to tell my friends and have them say with great concern in their voice, ‘Man! Ayo lucky.’

All the truck drivers and bulldozer and earth moving equipment operators became my good friends and I learnt to drive their huge machines. To drive a Caterpillar D9 dozer and literally move a mountain gives you such a kick that I remember the feeling even now, more than thirty years later. Men can’t move mountains, but they have invented machines that can. Such are the marvels of technology.

I have reason to remember the D9 and its power in a personal way as well. One day I was driving to Linden and decided to take a short cut through one of the Linden mines. As I was driving over the sand over-burden (this is what the soil that coves the ore is called) I suddenly started to sink in it. I put the Land Rover into 4 wheel drive and thought I’d get out fast enough. What happened, however, was that the vehicle simply dug itself into the sand right up to the axels and I was well and truly stuck.

As I stood there wondering how I would get out, I saw one of my friends in his D9, who having seen me, was driving towards me. When he came close he shouted over the noise of the engine, “Man! Baigie!! Get into your car and put it in neutral.” I yelled back at him in alarm, “Chinee!”

That was my friend Morris Mitchell’s nickname as thanks to large quantities of Amerindian and maybe even Chinese genes, he had the flattest face of anyone I have ever seen.

“What the hell do you think you are doing. You ain’t pushing my car with that dozer!! It will collapse.” “Man!! Ya do wa I tell Ya na Man!!” goes Chinee. So I got in and put the gear in neutral. Chinee dropped the blade of the dozer while he was a dozen yards away from the back of my car and built up a small hillock of sand between him and me. And this hillock of sand pushed the car out. The dozer did not touch it. Ingenuity of people who use these machines day in and day out.

The path through the forest that I mentioned earlier was one of the most interesting nature walks that I’ve ever taken. I would walk silently and suddenly come upon various animals and birds doing their own thing. The hummingbird hovering on invisible wings gently probing the center of a flower for nectar. The wings beat at such a speed that like the blades of a fast turning fan, they become invisible. Now the path was gone, claimed by its owner, the jungle.

One day walking down this path, I saw a boa constrictor, a young one about eight feet long, slow and lethargic after his meal, lying across the path basking in a rare patch of sunlight that managed to sneak through the forest canopy. He made a halfhearted attempt at getting away and then a fairly serious attempt at attacking me as I lifted him up and took him home. I built a square cage of 1” thick planks nailed together with big nails. Inside the cage I put a log of wood, which he would use to drape himself over. He seemed to like the arrangement especially as it was partially in the sun under which he liked to soak in the mornings. Boas eat only live prey and so every few days I would put a small chicken into the cage. The snake would lie as if he were dead. Totally still, so that you could not even see him breathe. The chicken, initially ruffled about its treatment and protesting loudly would quieten down and start scratching in the dust in the cage. Eventually it would hop onto the log right next to the snake. Talk of bird brains especially of farm grown broiler chickens who have never seen a snake in their lives. Then, suddenly, viola!! Magic!! In a flash, no chicken and a large lump in the snake.

I am very fond of animals and so I had quite a collection in Guyana. Apart from this snake I had a young Collared Peccary (a wild pig that lives in the Amazonian rain forests). This thing thought of me as its mother and followed me everywhere. I did not mind that but drew the line at him following me inside the house. So he would curl up with my boots which I left outside the door.

I had a young Tapir, which loved cassava (sweet potatoes) and I had a lot of trouble keeping him out of other people’s gardens, which would have been decidedly unhealthy for him and myself. But thankfully, Guyanese being as they are, though they loved tapir meat and hated anyone tampering with their vegetables, knowing that this thing belonged to me, they only yelled at it and sometimes at me. All this was done in a very friendly way. They would say, ‘Man!! Baigie, you should be with the girls. Instead, you walk around the forest by yourself and collect these animals. Okay, so eat the thing man!! Or call us and we gonna cook he for you. But na!! You gotta keep he as ya frien. You need a gyurlfrien man!! Not a tapir!!’

One day one of them asked me, “Man!! Yawar, ya raas aint got no guyrlfrien, you ain’t married, you don’ drink, tell me why you alive, haan??” Then he got philosophical and asked me, “A’yo Indians all like dis man?? Then tell me how come you so many?? How you mak alladem babies man??” Simple people with good hearts were my friends from Kwakwani.

I recalled how we used to travel from Linden on the rickety Kwakwani bus with Joyleen Crawford as the conductor and George Sears the driver. I remember these two very well as they used to bring the mail from Linden for which I used to wait like a fish out of water….out of breath. Kwakwani people never understood why I, a bachelor and a very eligible one at that (young, nice looking, had money, a regular job, etc. etc…..) was never interested in the Kwakwani girls. Joyleen tells me today (she mailed me one day in 2010 having seen my address in some other mail and said, “Yawar is that you??”) that all the girls of Kwakwani used to bet with each other to see who would get me. None did, and I did get very lonely sometimes. Lonely and depressed, yearning for companionship that never came through. The night outside was dark, as I sat on the veranda gazing into the shadows of the orange orchard, listening to the sounds of the jungle around my home. The night inside me was darker still, strange forms and shadowy shapes in the murky depths. Menacing and frightening and I, without the cognitive tools to deal with that. It is when I reflect on those days that I realize how Allah gave me the strength and support when there was nobody else. Today I realize that His plan for me was better than my plan for myself. I recognized my Rabb in the breaking of my dreams and learnt to trust Him and the inner voice in my heart more than the noise of my desires in my ears.

In those years, I learnt the meaning of rejection, parting, and loss. I also learnt how to pick myself up from the depth of depression and rebuild my self-esteem, not on the shaky basis of other people’s opinions, but my own assessment and acceptance of myself. I learnt to like myself, to forgive myself, to hold myself accountable for what happened to me, and to stop blaming others. I learnt that it was I who was in control of my feelings. Other people could do whatever they wanted, but that it was I who had the authority to decide what I wanted to feel about what they did. I learnt the freedom of saying to myself when someone did something unpleasant, “I will not allow him or her to decide how I am going to behave or what I am going to feel.”

People may be abusive. We choose to feel hurt because we accept what they say about us. People may reject us or treat us as less than themselves. But it is we who decide to agree with them and feel bad. People may feel threatened when they encounter us in work situations because we challenge them when we demonstrate our own competence. We feel bad about their reaction, but fail to realize that to pretend to be incompetent to please someone else’s ego is not an option. I learnt that the key is to realize that it is we, not they, who define us.

Nobody can MAKE us feel anything. We feel whatever we choose to feel. People don’t like to accept this fact because with it comes the understanding that if I am feeling bad about something, then I am the one who is responsible for it. It is either a frightening or a freeing situation, depending on how we choose to look at it. It is frightening if we refuse to stop looking around trying to find someone to blame for what is happening to us. It is freeing if we choose to realize that if we are in control then we don’t need to feel bad if we don’t want to. Slavery is comforting and freedom is frightening to many people, so they go around feeling bad and blaming others for what happens to them, refusing to recognize their own role and responsibility in it. Not willing to face the fact that this attitude only makes matters worse, not better. Typical ‘victim’ mindset.

Another game we play with ourselves to justify inaction and copping out, is to express the problems we face in global terms. We talk about the problem as if it is a problem of the world. We say, “This is the problem with people today.” Whereas the reality is, “This is my problem today.” Let me illustrate. If I say to myself that the biggest problem for the Third World is poverty and a lack of education. Then you ask me, “So what can you do about it?” I feel justified in saying, “Well, I am one man. What can I do to solve the illiteracy problem of the Third World?” But instead of this, if I define this problem to say, “Can I educate one child other than my own?” Then the problem is solvable. If I do this and I spread the word to others and encourage them to pay for the education of one child, then eventually we will see the impact of this on the global screen.

We globalize issues because the solution also becomes global and then we feel justified in feeling helpless and in sitting idle and taking no action to solve the problem. But if we choose to redefine the problem in personal terms, we will find that there are solutions where we did not think they could exist. The issue of course is that it then becomes very uncomfortable for us to sit by and do nothing. We are forced to take action and in that is hope for the world.

I decided in those years that I would consciously choose the ‘Master’ mindset in every situation that life may put me in. I did not know these terms then. I invented them more than 20 years later. But they are grounded in the throes of personal growth and the pain of accepting my own personal power. Strange to see how accepting that you are powerful can be painful. But there it is!!

If we think about it, in every situation, no matter how many things are actually not in our control, there are always things that are in our control. At the very least, how we choose to feel about the situation is in our control. How we choose to behave in that situation is always in our control. To ask instead of telling, to offer instead of demanding, to contribute instead of consuming, to stand instead of running, to respond instead of reacting, are all in our control. What we choose to speak or do is in our control. To choose to do nothing is also a choice and that too is in our control. Take a simple matter like being stuck in a traffic jam. Most people start fuming, their blood pressure rises, they start getting restive, then irritated, and then furious because someone accidentally honked. Road rage statistics in the US show that the maximum number of cases of verbal and physical violence happen in traffic jams. And at the end, you are still stuck.

However, there are those who use the same situation and time to catch up on reading, some meditate, some pray, some actually start conversations, and make friends in traffic jams. All in the same situation as those who are ready to kill each other. Lesson? It is our choice whether we want to treat our situation as a problem and complain or as an opportunity that hardship provides and take advantage of it. Problems need solutions, not complaints.

For more please read my book, “It’s my Life”

It is our choice whether we want to treat our situation as a problem and complain or as an opportunity that hardship provides and take advantage of it. Problems need solutions, not complaints.

PURE GOLD,,,!!