I breathed a huge sigh of relief as we loaded the last railway sleeper on the barge. The beginning of this barge story goes back to when I first arrived in Kwakwani and saw the mining operations. Bauxite mining is done by the open cast method, which is one of the most wasteful and destructive methods known to man. But it made economic sense and long-term effects were not on anyone’s mind, so it went on. The sequence of operating an open cast mine is as follows. First the prospecting team identifies where the bauxite ore deposits are. They do this by drilling holes on a grid pattern and analyze soil samples sometimes from several hundred feet underground. This enables the geologists to create a map of the underground ore deposits. The prospecting team stays deep in the rain forests away from habitation for several weeks at a time. Food and supplies would be trucked in, to them from Kwakwani. Loneliness was a major issue and alcoholism its outcome. The prospecting teams welcomed visitors and I would often spend a weekend with them. One day when I was with one of the teams in the forest, one of the Amerindian drillers came to me looking very agitated and said, “Man Baigie, I want a week’s leave.” I knew he had no leave to his credit and told him that he could not take leave. He begged and pleaded, “Man!! A bin out ‘ere in the jungle too long man. I miss the ol’lady baad man. You raas na married, wa ya know about all dem ting!” I was not getting into a discussion about the need for female company so I stuck to my guns and told him that he had no leave to his credit and so he could not go. Eventually he became such a pest that I said to him emphatically, “Leon, I told you, you cyan go.” That got to him. He pulled himself up to his full height of 5 foot nothing and said to me, “Man Baigie, you cyan tell me I cyan go! You can tell me I cyan come back. But you cyan tell me I cyan go!!” I was so amused at this obviously logical explanation that I burst out laughing and said to him, “Alright off with you for three days. I will look the other way. Unofficial leave.”

The Amerindians were simple people who lived from day to day without a thought for the future. They worked when they were hungry and relaxed when their belly was full. Alcohol was the bane of their lives, but they were oblivious to that. Once an area had been mapped and it had been decided to start mining, the forest would be cleared in preparation for mining operations. This was done by simply sending in Caterpillar D9 bulldozers (each the size of a small house) which would push over all the trees into one big pile which would then be set alight. Sometimes these fires would burn for months. Then the dozers would clear the overburden, which was mostly sand, until they reached the hard pan. Then the Dragline Excavator would come in and start digging. The Dragline Excavator is such a huge machine that it has no wheels or tracks but actually ‘walks’ on huge feet. It is an amazing sight to see a Dragline Excavator moving. Eventually a colossal pit would be created with the Dragline Excavator sitting in the middle of it, deep below the level of the surrounding forest, like some pre-historic dinosaur working round the clock digging out the ore. The Dragline Excavator would load the ore into huge Caterpillar trucks with a payload of 50 tons which would cart it away to the crusher. The crusher would crush the ore into a uniform consistency and load it onto barges that a tugboat would then push down the Berbice River to New Amsterdam to the calcining plant. For those interested, this is what calcined bauxite is: Calcined Bauxite is produced by sintering high-alumina bauxite in rotary, round, or shaft kilns at high temperatures. This process of calcining (heating) bauxite in kilns removes moisture and gives Calcined Bauxite its high alumina content and refractoriness, low iron, and grain hardness and toughness. Its thermal stability, high mechanical strength and resistance to molten slags make Calcined Bauxite an ideal raw material in the production of many refractory, abrasive and specialty product applications.

I often tried to imagine what the whole opencast mining operation would look like to someone from another planet flying overhead. They’d see a huge hole with a living creature with a long neck and a wide jaw with massive teeth, sitting in the center of it, continuously biting out large chunks of the earth and spitting them into waiting trucks. Once the truck has its payload it drives up out of the hole up the carefully graded road often circling the pit a couple of times as the road climbs out of the depths of the earth. A hairy operation as the road had no safety barriers (not that any barrier would hold a fifty-ton truck) and the pit yawned on one side of it. It is a tribute to the skills of the drivers that in the five years that I lived in Guyana there was not a single major accident. When the truck comes out over the lip, it drives swiftly through the forest and eventually dumps its load at the ore dump near the crusher. Then back to the pit. At the ore dump are the Front-end Loaders, huge machines on wheels with a toothed bucket in the front. This scoops the ore from the pile into its bucket, turns around and trundles along a few meters and dumps it into the hopper of the crusher. Then it would spin in its track and back to the ore dump for its next load. In the middle of all this would be another machine that resembles a large beetle called a Scraper. That is what it does. It scrapes off the topsoil (called overburden) into a hopper that is in its belly and then it takes it and dumps it away from the main pit.

Then there is the Grader that ensures that the road remains clear, level, and smooth so that the trucks can run without interruption. It is amazing how many of these machines resembled insects. This process would go on, day and night, continuously. As I mentioned, opencast mining is perhaps the most destructive operation on earth. In Guyana in those days there was not even an attempt at rehabilitating the land, so when a pit had been mined out, it would simply be abandoned. If you drove around you would come across many such mined out pits filled with the clearest, bluest water you ever saw. This was the result of the minerals in the water, one of the effects of which was that nothing lived in the water. The water was good to swim in and we did that often. The pits were very deep, so it was not totally safe to swim in them, but when you are twenty-some years old and there are others swimming with you, you don’t think about safety. Not the wisest thing to do, but I lived to tell the tale.

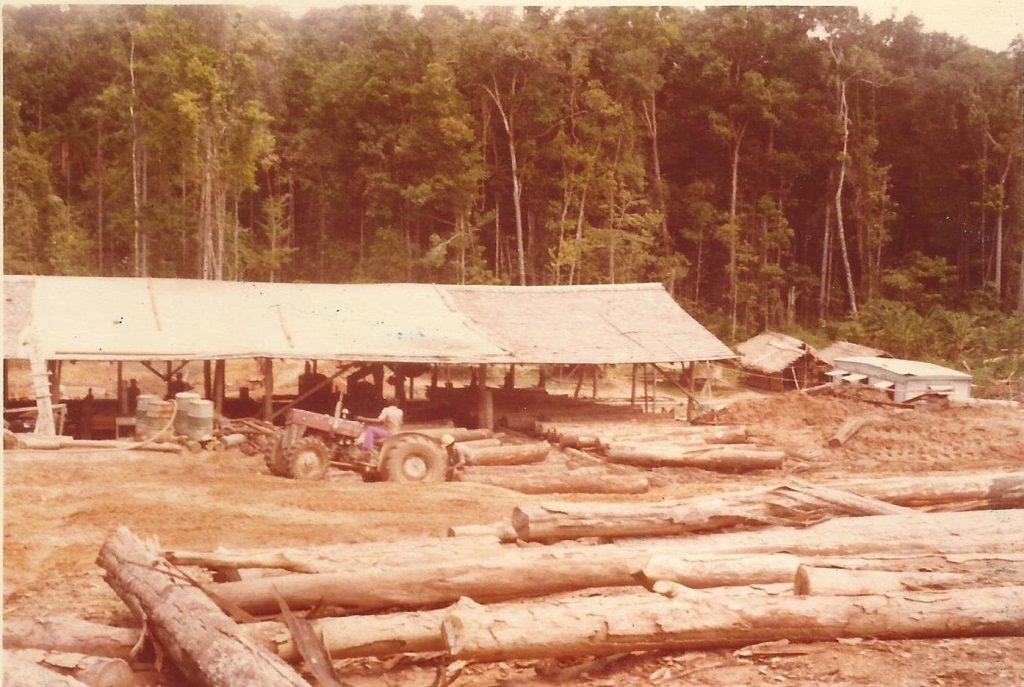

When I started working in Kwakwani and learned something about the forests, I realized that just as I had suspected these forests had good hardwood trees. Good for making furniture and construction material, but nobody had the time to do anything about that and so they simply burnt them to clear the land to get to the ore. What this burning did to the environment is a different story and to tell you the truth, I was as unaware in those days about environmental issues as most other people. What was obviously clear though, was that a lot of otherwise useful timber was being wasted simply because nobody was interested in doing anything about it. The core operation of the company was mining and that was all that any of the managers was interested in. I made a proposal to the company that we setup a sawmill operation, which would be able to utilize this forest resource and be a self-sufficient, profit making business.

The management agreed and this sawmill operation was given to me to run in addition to my regular job as Assistant Administrative Manager. My boss, Mr. James Nicholas Adams (Nick Adams) was a remarkable man who was also my mentor and guide. Although he was technically in charge of the whole operation, he let me run it the way I wanted and that was a tremendous learning opportunity for me. Nick had a unique way of teaching by delegating responsibility and then periodically calling me to do a participative analysis of my own performance. He would then reinforce the strengths and achievements and encourage me to draw lessons from my mistakes. I remember my first ever appraisal in 1980. Nick gave me the form and told me to fill it in myself. I was shocked because I thought appraising was something that the boss did of your work. But Nick’s point was, ‘You know what you did better than I did. So, write it up.’ I returned with what I thought were my achievements and then Nick and I had a long chat about them. Thanks to my Indian cultural upbringing, Nick ended up adding several things that I had left out feeling that they didn’t really count. I still have that form with Nick’s signature on it, from 1980.

One of my major learnings was that responsibility, variety, challenge, and satisfaction in a job are largely in your hands if you use your head and can influence people. I was not the only person who saw the way the forest was treated or who saw that timber that was being burnt could become an independent source of income. I was the only one who translated these thoughts into a workable business model. The result was that it was added to my responsibility and I now had an official reason to spend time in the forest. I recruited my good friend Peter Ramsingh to be the head of this operation and Peter and I spent the next five years doing what we loved to do anyway – wander in the rain forest at will. I recruited Amerindian workers, who knew the rain forest of the Berbice River valley like the backs of their hands, for the sawmill operation. These people lived a nomadic life in the forests in semi-permanent camps. They would clear a small area of the forest and grow a few vegetables, and hunt deer, collared peccary, capybara, and agouti that came to feed on this new bounty in the forest. They knew the location of each Greenheart, Wamara, and other hardwood trees in the forest, which they came across in their wanderings. Ideal people to do the scouting operations that we needed to locate the trees we needed for the mill. Once they had located the trees, the extracting team would fell and haul in the trees. I recall with mixed feelings the day when one of the Amerindian scouts offered to show me a magnificent Greenheart tree that he had located. We started off at about 8.00 a.m. I told him that I had to get back to the office as I had some work and so I hoped that the tree was nearby. “It dey right hey. We gon get dey jus now!” he said. He said the same thing all through the day as we walked through the forest, following a track that only he could see and eventually reached the tree at 4.00 p.m. There was no way to return to the office that night and so we camped at the foot of the tree until the following morning. There is always water in the rainforest, if you know where to look, so we weren’t too badly off. There was nothing to eat, but then food is not critical to survival. Time and distance had no meaning for our Amerindian friends. Or maybe they had a different meaning from ours.

Peter Ramsingh was a man of enormous energy, enterprise, and initiative. Peter got along well with his people and became the ideal manager of the mill. Peter and I would spend hours in the forests, accompanying the scouts in their explorations, not because they needed our help but because we both loved being in the rainforest. The interesting thing is that nobody ever used the term, ‘rainforest’ in Guyana. Or even ‘forest’. It was always ‘bush’ or ‘backdam’. Peter’s wife Chandra would send me things she cooked and would pack us lunch when we took off on our jaunts. Chandra was Nick Adam’s secretary and a wonderful, patient lady with a big smile always on her face. To this day, 30 years later, I can still recall the smell of the vegetation in the dim recesses of the Berbice River forests, so thick in places that the sun did not penetrate to the forest floor. It was with great distress that I learnt in 2009 that Peter Ramsingh had died of congestive heart failure in 2001. One more, dear friend gone forever. Feeling the pain of parting is the price of friendship. Peter was a truly dear friend whose memory I honor and remember every time I think of Guyana.

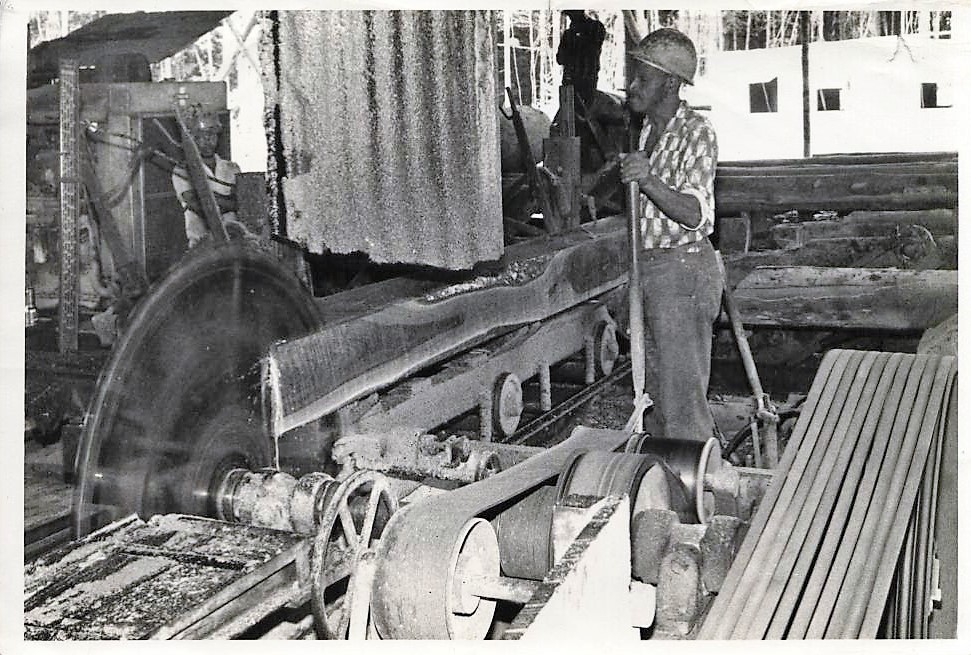

Once the sawmill had been set up, we went order hunting and the first big order we received was from the mining railway for sleepers as they were renovating their tracks in two locations. We were very excited as this would make our sawmill profitable and prove the point on which I had projected the whole plan. The only hitch was that the sleepers had to be sawn and shipped out of the ‘backdam’ (Creolese for forest) to the waterfront loading point by a particular date, and loaded on the barge which would take them to New Amsterdam. All material came to Kwakwani by river boat which took back bauxite ore on the return trip downriver. There was much excitement and lots of long hours of work in felling and extracting the trees from their different locations, dragging them to the mill and then sawing them into railway sleepers. Mr. Gibson was the man on the circular saw at the mill. He was very skillful in carving out the maximum number of sleepers out of a log. Once the sleeper had been sawn it had to have two 8-shaped irons hammered into either end to prevent splitting. Since we were extracting individual trees of a particular species from the rain forest, (as distinct from plantation felling) we had to find the tree, fell it, and extract it. The machine used was called a Skidder, also made by Caterpillar.

The Skidder was a very versatile machine with a dozer blade on the front end and a large crab-hook at the end with a steel rope and winch. Once the tree had been felled, the Skidder operator would drive up to it, in the process making its own track, hook the tree, loop the steel cable around it and winch it up to the platform on the rear end. Then the machine would drag it to the mill. Very efficient and fast but also very wasteful as the machine left huge swathes of crushed vegetation in its wake.

The difference between mechanical and ‘biological’ extraction became even more starkly clear to me when, several years later in the Anamallais (Tamilnadu, South India), I went to see some timber extraction operations being done by the Indian Forest Service, using trained elephants. The way the animals and their mahawats worked with an almost telepathic bond, was amazing to say the least. And the economy with which individual trees were extracted was simply delightful to see.

To come back to our story, we had all the railway sleepers ready and stockpiled at the waterfront in time when the barge arrived. Now to the tricky part – twenty-four thousand sleepers had to be loaded onto the barge in 24 hours when it was due to leave. Our innovative solution – work straight through. And that is what we did. I mean the ‘we’ literally as I loaded the sleepers, physically, with the loaders. We would take breaks every two hours, eat bread, and cheese and drink large mugs of sweet, milky, tea and then get back to work.

Guyanese being what they are, someone started a very ribald chant in a catchy tune that others took up and that was the beat we worked to. Hours flew by, night fell, and our willing electrician rigged up some makeshift lights so we could continue to work. And we worked. Come sunrise, the last sleeper had been loaded. We were all dog tired with aching backs and bruised hands, but not much the worse for wear. I was young and tough in those days. We headed off to our homes for a hot bath and eight hours of sleep straight through.

What was remarkable about this story was that in the highly unionized environment of the Guyanese bauxite industry, there was not a single protest from the union about making people work beyond hours or for overtime wages or anything at all. Later one of the union stewards told me, “Maan Baigie! Your raas make aa-we shut up maan. You was dey with de bais loading sleepers and eating wat dey was eating. Wa cud we say maan?? Your raas smart!!” Which, translated reads: You made us shut up. You were there with the boys loading the sleepers with them and eating what they ate. What could we say? You are smart.”

Now the big secret is that I did not do that because I was applying strategy, but because that is how I work. I never ask anyone to do what I would not do myself and as it happened, it is also good leadership strategy. Leading from the front. Demonstrate the standard, not merely talk about it.

However, this strategy did not always work in Guyana. I remember my friend, Rev. Thurston Riehl. Father Riehl told me this story about the time when leading from the front didn’t work. He was an Anglican priest, Vicar of Christchurch, in Georgetown. The interesting thing was that Father Riehl had a parish that extended up the Berbice River for more than a hundred miles. He had a motorboat in which he used to go up and down the river, often alone with only the sound of the outboard motor for company. He was an accomplished naturalist and had a wealth of information about the rain forest and its flora and fauna. When he learned that I was interested in the same things, he and I would spend many hours walking in the rain forest where he pointed out various things to me. He once told me, “When God finished creating Hell, he threw all the leftovers in the Amazonian rain forest.” This referred to the many charming creatures that live in these parts. From tarantula spiders, to sting rays, electric eels, piranhas, vampire bats, boa constrictors, anacondas, bushmaster, black and green mamba, boomslang and an amazing variety of snakes.

Of course, the forest has its share of beautiful creatures as well; scarlet and purple macaws, toucans, parakeets and parrots of many types, Sakiwinki monkeys (also called Squirrel monkeys – very small with large eyes), flying squirrels, hummingbirds the size of moths which beat their wings at anything between 15-90 beats per second, sun birds whose fluorescent plumage shines in the gloom of the rain forest. Forest sounds that I used to look forward to were the booming call of the Howler monkeys echoing in the early morning mist, the raucous calls of macaw pairs who mate for life, flying to unknown destinations, talking to each other in flight.

I was (and have always been) very fond of animals and had all kinds of unusual pets. In Guyana, I had the opportunity to indulge myself because I lived in the middle of the rain forest and there were no restrictions on what I could and couldn’t own. If I could catch it, feed it and keep from being eaten or bitten, I could keep it. I had a boa constrictor (12 feet half grown), a Toucan, a free flying Scarlet Macaw, a Tapir, and a Sakiwinki (Spider) monkey as pets. I also had a large number of hens, Muscovy ducks, and turkeys, which were pets until they got converted to food. The ducks were not very good to eat, too tough and also hard to catch as they were feral and free flying. But the turkeys and chickens regularly added to the larder. Female turkeys are obsessive incubators of eggs. They will sit on anything spherical. I once found a turkey that was trying to hatch an electric light bulb which to its intense disgust refused to oblige. On another occasion, I was searching for a missing turkey after a rainstorm and eventually found it sitting in a hollow in the ground where it she had laid her eggs, with water up to its chin. The crazy bird refused to leave its nest and was sitting on the eggs with just her head above the water. Such were the incidents of my life…small pleasures that added value, conversation, and fun.

Berbice was a very poor region with most people farming in the forest. This consisted mainly of slash and burn agriculture where people would grow cassava, yams, bananas, peppers, and pineapples. It’s called slash and burn because that is exactly what the aspiring farmer does. He slashes a piece of forest, leaves the chopped trees and bushes to dry for a few days and then sets them on fire. This fire burns for a few days and leaves behind rich potash with acts like fertilizer. The farmer then plants his crop in the cleared area and gets a bumper crop from the forest soil rich in humus and ash from the burnt trees. However, that is only for a couple of rounds by when the rain leaches out the nutrients and the soil reverts to its original sandy state. Then the farmer moves on to a new patch to repeat his cycle. This is how the rain forest gets inexorably destroyed, patch by patch.

In the Guyana of the 70’s, ideology (communism) ruled everything – including what you could grow, sell, or eat. Potatoes were considered signs of the colonial masters (they were called Irish Potatoes – even though they had been brought to Ireland from South America) and were therefore illegal to grow. Some farmers in the bush would still grow them clandestinely. I remember we would sometimes get a gift of 2-3 potatoes, which someone had either managed to grow or smuggled in from Suriname. The lesson that value is in the eyes of the perceiver was something I learnt early in life.

One of the things Father Riehl wanted to do was to teach his parishioners some skill by which they could make some more money and improve their standard of life. As there was a ready market both for eggs as well as poultry and Guyana is a high rainfall area, he thought that duck farming would be a viable idea. The only issue was the need for some kind of reservoir of water without which the ducks wouldn’t lay eggs. His parishioners lived on the River Berbice but the main river with piranhas, caiman and anacondas, was not the best place to farm ducks. So, the potential duck farmer would need a reservoir that was safe for his ducks. When Father Riehl mentioned this idea to his parishioners, they typically said, “O! But father, we cyan do nothin! Whay awe gonna ged da tank?” I can still recall the lovely sing-song tone of voice these people of Berbice spoke in. Father Riehl thought that he would teach them some lessons of self-help by example. He got himself a spade and a pickaxe and marked out a large roughly circular area and started digging.

He said to me, “Every morning I would start digging and people would stand around and watch in friendly silence. They would make appreciative noises and comment to each other, ‘Father Riehl, he wok so hard!’ They would bring me water to drink and would offer me lunch and dinner. Nobody more hospitable than Guyanese and out of them, my favorites, the people of Berbice. I lived among them as one of them and so all Berbice people were family. The whole day would pass and, in the evening, when the work stopped they would make a lot of appreciative remarks about how hard I had worked and the tremendous progress of the hole in the ground. Then came the day when it was finished, and we let water into the pit. It filled up nicely and all that remained was to get some ducks. But I wanted to be sure that they would take this on and replicate this work, now that they had seen how easy it was. But when I asked them, they said, ‘O! Father, but we cyan do dis.’ I was flabbergasted. In shocked surprise I asked them, ‘But you saw me do this. So, you see that it is something that you can also do. What is the problem?’ They said, ‘O! Father, but you’z differen!!’

Guyana was ‘differen’ in many ways. Amazonian rain forest, exotic wildlife and birds, people who were very friendly, and whose life was as untouched by the rest of the world as is possible to be.